Anyone who knows me, or is unfortunate enough to be taught by me, knows I am a slight Empire nerd. Studying the British Empire is important in History, in order to give students a grounding in the footprint that the United Kingdom has on the world: past and present. It is a very nuanced footprint, and the term “empire” means different things in different countries and illicit different responses. Even within Britain itself.

Post-Colonial studies took the concept of the “male gaze” from film theory, an interesting theory about the role of women in film and the power that man has within the industry on screen and off screen, and placed the idea of a gaze into the study of Empire. As Schroeder puts “to gaze implies more than a look- it signifies a relationship of power in which the gazer is superior to the object of the gaze” [1]. E Kaplan uses the idea of “Imperial gaze” to look for the “other” in Hollywood (I like to think of it like the eye of Sauron because who does not love a Lord of the Rings reference?) and that the Imperial gaze reflects that the white gazer is central [2]. Therefore the “imperial gaze” places the white western gazer in the central focus, giving them the power to interpret what is within their line of sight. The Imperial gaze can be preformed by any gender, what is core to this idea is that of coloniser and colonised- gazer and gazee (I have made that word up).

Therefore sources used to examine Empire will in some way reflect this theory of the Imperial Gaze and will present (or not present) the colonised in certain ways. As a result, I do think it is important to show a variety of sources in teaching Empire, from the Gazer but also ensuring that the stories of the object of the gaze are told still. It could be interesting to design lessons around Empire, looking at stories of those colonised first and then comparing these stories to images (or in some cases the absence) of images of those stories in the Imperial gaze.

Over my time studying Empire, I have come to really like some sources/ stories. These sources and stories have stuck with me over time, made a lasting impression and end up blurting out in some of my daily conversations. I also use most of them in my own teaching. Some of these stories are subjugation and punishment, some are stories of triumph and resistance and others are people finding their way in an Imperial world.

- Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

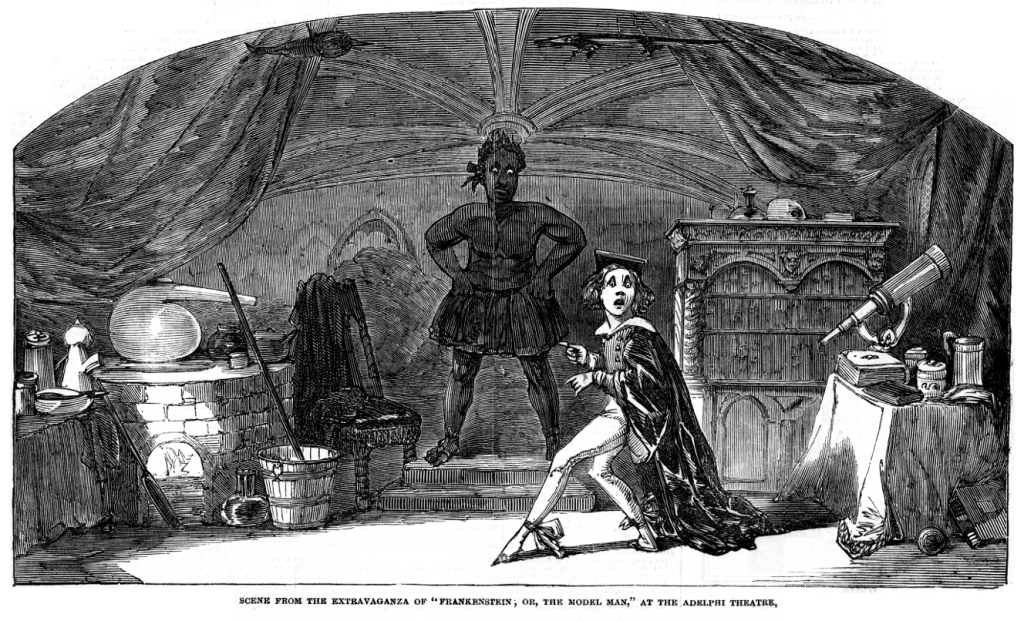

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is a staple read in many schools, and the Gothic genre is fascinating to look at, mainly due to the rise of the genre in the Victorian era, coinciding with Malthusian fears about the populations, fears of working class rebellions, fears of the “other” in colonial spaces and fears about family. The Gothic genre at the time represented the central tensions of an age where there was increasing social liberation and political revolution, resulting in profound change in society as a whole. Mary Shelley was the daughter of an abolitionist, and no doubt would have had some exposure to abolitionist thought, but also wider viewings of Empire. Frankenstein gives an interesting gaze on Empire, as there is an interpretation of the work through a racial lens; with Frankenstein’s Monster representing a slave. [3] This is interesting but also contradictory as the text describes him as having “translucent yellow skin”. However certain plays or images at the time would play on the idea of race, showing the monster as a large black man, shown down below. But what ties more into the slave narrative, is the complex relationship the monster has with the rest of the world and indeed Frankenstein himself.

It could be really interesting to include this viewpoint, especially if the English Department teach this text and it could deepen the value of interpretations and debates around it.

2. Charles Darwin “The Beagle Voyage Diaries“

I am hesitant to say this, but I don’t think Empire can be understood without looking at the emergence of racial attitudes closely linked to Empire at the time. This includes Charles Darwin known for his monogenic ideas in the “Origins of Species” and his voyages on the Beagle. Social Darwinism has been accredited to his work, but i have often heard it thrown around that Darwin would not have intended his work to be used to justify racism and colonisation. His diaries do show otherwise, and are a fascinating insight into the mindset at the time but also a very young Darwin’s first experiences of the wider world. Here are my favourite quotes from his experience around Tierra Del Fuego, an archipelago at the tip of South America:

In the afternoon we anchored in the Bay of Good Success. While entering we were saluted in a manner becoming the inhabitants of this savage land. A group of Fuegians partly concealed by the entangled forest, were perched on a wild point overhanging the sea: as we passed by, they sprang up and waving their tattered cloaks sent forth a loud sonorous shout. The savages followed the ship…. It was without exception the most curious and interesting spectacle I ever beheld: I could not have believed how wide was the difference between savage and civilised man: it is greater than that between a wild and a domesticated animal.

Chapter 10: Tierra Del Fuego, The Voyage of the Beagle, Charles Darwin

But these Fuegians in the canoe were quite naked, and even one fill grown women was absolutely so. It was raining heavily, and the fresh water, together with the spray, trickled down her body…. A woman, who was suckling a recently born child, came one day alongside the vessel, and remained there out of mere curiosity, whilst the sleet fell and thawed on her naked bosom, and on the skin of her naked baby! These poor wretches were stunted in their growth, their hideous faces bedaubed with white paint, their skins filthy and greasy, their hair entangled, their voices discordant and their gestures violent. Viewing such one can hardly make one’s self believe these are fellow-creatures and inhabitants of the same world.

Chapter 10: Tierra Del Fuego, December 25th, The Voyage of the Beagle, Charles Darwin

There is a lot to unpack just from those two quotes, and therefore so many different things to pull from just these two quotes. Victorian manners was central to society at the time, and these manners were seen as a way of the civilised. The colonised, or those yet to be colonised, lack those manners and thus civilisation within this gaze. Matching the lack of manners, were the dress of the tribse and in particular he fixates on the women. He had a fascination for naked women, due to lack of shame and therefore what is common throughout his entries is a sexualisation of the women he encounters as the object of his gaze. Also he had a habit of naming those who accompanied him, as translators or guides with mock names (York Minster as one example) and in naming them has power over them.

3. Saartje Baartman

Entertainment has always been popular, but during the Victorian era there was a growing rise in the curiosity of monstrosity as a form of entertainment. Many of the Exhibitions made post 1850, mainly the 1886 Colonial and Indian Exhibition, would use “human zoos” as a focus point, allowing the public to gaze on different colonial spaces from the comfort of the exhibition.

Saartje Baartman’s tale is an example of an earlier form of this entertainment, one that many people do not know about, showing an absence of her story from some people’s understanding of Empire. Baartman was of Khoi Khoi descent and chosen to tour around Europe to show off her pronounced features: her bum and genitals. She was known as the “Hottentot Venus” – a reference to the goddess Venus but also a racial epithet for those descended from the Khoi Khoi and now highly offensive and rightfully so! She was toured around Britain and France, ogled at by the white gaze as a “monstrosity” and people began to wonder if this woman held the missing link between human and animal. She was highly sexualised, and her body became a focus of the rise of scientific racism, ideas of climate affecting bodily features and function. She died aged 26, but instead of getting a funeral and burial, her body was sold and used to try and find this missing link, her remains linked in findings to those of monkeys.

Her body was returned to South Africa in 2002 and finally laid to rest after 200 years.

Saartje’s story is a sad but important one: as a woman of African descent her story shows how the white world viewed and treated women as objects of desire, but the added element of her skin colour resulted in a form a racialised desire. Her body was used to justify racial ideas emerging, justify the colonial mindset and fetishised her.

4. Lakshimbai Rani of Jhansi

I have already included her story in my piece reflecting on the current debates about Empire, but her story is so badass I have to include it again.

1857 was a year that saw mindsets towards Empire change with the Indian Rebellion, followed by the British shut down of East Indian Company control and the swallowing of India into a colony. It was triggered by rumours of pig or cow fat, being used on the Enfield Rifle, which required the user to place the cartridge in their mouths to use the gun. This upset the Hindu and Muslim Sepoys, who then rebelled. However the British had for a long time stoked discontent in India: debates about the use of Education to civilise people, Lord Dalihousie establishing the Doctrine of Lapse which allowed the EIC to take over areas of land from Indian Princes who were not children of blood to the previous Prince to name just a few.

She was widowed in 1853, but her husband had adopted a son and had set in motion the paperwork to ensure his estates would pass to his adopted son. In 1854 Lord Dalihousie refused to acknowledge the adoption as legal and seized the land of Jhansi under the Doctrine of Lapse. During the Sepoy rebellions, those in Jhansi rebelled and the British were quick to blame Lakshmibai. She escaped Jhansi at night, with her adopted son strapped to her back and joined the rebelling forces. She would lead the remaining Jhansi soldiers into battle dressed in male attire on June 16 1857. She was killed in battle.

The Imperial gaze treated Lakshmibai with a duality: one the hand the “Jezebel of India” but on the other a Joan of Arc figure. Unfortunately for the rest of the rebellion, newspaper spread false reports of their actions often presenting the Indians as pillaging their way through British settlements. [4]

5. James Douglas

James Douglas was born and raised in Demerara to a free Black mother, educated in Scotland and spent most of his life living in North America in Canada. He held powerful posts in the Hudson Bay Company and served as governor of the British colonies of Vancouver island and British Columbia marrying into a prominent Metis family (indigenous group of Canada).

His story shows how a Creole man was able to rise to elite status, but also the collection of his diaries and letters show the politics of home: both domestic and national, but also how his situation disconnected from the typified ideas around race, nation, empire and gender that was prominent in the nineteenth century.

Although there are elements of his story that are not clean cut, existing within the nuances of the time, his story is a fascinating one to look at. I urge you to check here if you want to know more: https://bcblackhistory.ca/sir-james-douglas/

6. Mary Prince

The stories of former slaves used by Abolitionist is another area that isn’t clear cut. On the one hand, Abolitionists worked to end slavery and later bring light to the treatment of aborigines in the colonies, the works of Buxton highly influential in achieving this. On the other hand however, they would use the testimonies of former slaves to highlight the injustice yes, but also to serve for a larger motive. As seen with Olaudah Equiano (the more well known) and also with Mary Prince, these former slaves could write very well constructed accounts of their servitude- using excellent English, well spoken but also appear to present in a “civilised manner”. In other words: they were dressed up and acted white in order to support the argument that Abolition would not result in a bunch of uneducated “savages” grounding the economy to a halt or worse revolting against colonialism like in Haiti.

This is highlighted more so with the story of Mary Prince than others, as she was not allowed to partake in the meetings of the Abolitionists despite the fact her written work was published in 1831 used to further the cause. She never had a direct voice in the group of white abolitionists. Within the Abolitionist narrative, it is interesting to see the focus on religion and morality, but there was a disconnect between freedom and equality. Equality was never really something that was thought about by the Humanitarian movement until later.

Mary Prince’s diaries are fascinating to show how to the contemporary audience slavery was still a prominent force in the early nineteenth century and like other accounts before hers, hers was a success- Slavery was abolished 3 years later (more like 7 if you take into account the Apprenticeship system).

When I reached the house I went directly to Miss Betsey. I found her in great distress; and she cried out as soon as she saw me: “Oh, Mary! My father is going to sell you to raise money to marry that wicked woman. You are my slaves and he has no right to sell you…” …. Oh dear! I cannot bear to think of that day- it is too much- It recalls the great grief that filled my heart, and the woeful thoughts that passed to and fro through my mind, whilst listening to the pitiful words of my poor mother, weeping for the loss of her children….

The History of Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave, related by herself (London: Westley and Davis, 1831)

I got no sleep that night for thinking of the morrow; and dear Miss Betsey was scarcely less distressed. She could not bear to part with her old playmates and she cried sore and would not be pacified… “See, I am shrouding my poor children; what a task for a mother!” – Then she [her mother] called Miss Betsey to take leave of us. ” I am going to carry my little chickens to market” (these were her very words)

The History of Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave, related by herself (London: Westley and Davis, 1831)

I have always preferred Mary Prince’s accounts to others, as I find hers easy reading and you get a real sense of her character in moments of her writings. I also like to subvert the idea of the Imperial Gaze here, to give Mary Prince power. With her narrative, despite the fact it was used by the movement, she is able to hold an institution of slavery within her gaze and make that the object, giving herself ownership over that experience within her narrative.

Reading:

1. Schroeder, Jonathan (1998). “Consuming Representation: A Visual Approach to Consumer Research”. Representing Consumers: Voices, Views and Visions. New York: Routledge. p. 208

2. Kaplan, E. Ann (1997). “Looking for the Other: feminism, film and the Imperial Gaze” (Routledge)

3. Machlow, H. L “Frankenstein’s Monster and images of race in nineteenth century Britain” (1993)

4. Toler, Pamela “Who is Manikarnika? The real story of the legendary Hindu Queen Lakshimibai” (Sept. 2006) [https://www.historynet.com/who-is-marnikarnika-legendary-hindu-queen-lakshmi-bai.htm]